Posted November 24, 2015 by Rachel Smith

Hawai‘i is known as the endangered species capital of the world. Home to some of the worlds rarest plants and declining numbers of endemic birds, Hawai‘i’s ecosystem is delicate but rich in biodiversity. According to the Hawai‘i State Department of Land and Natural Resources, nearly 90 percent of the 1,400 Hawaiian endemic plant species are found no where else in the world1. And while the state of Hawai‘i makes up less than one percent of the United States landmass, over 40 percent of the nation’s threatened and endangered plant species are found in Hawaii.

Almost none of the native bird or plant species in Hawai‘i have defense mechanisms – they never needed to protect themselves. The island chain is more than 2,000 miles from the nearest land mass, and Hawai‘i endemics evolved over the course of millions of years in a peaceful environment. Until the first humans arrived, native plants and birds in Hawai‘i co-existed in harmony, and had no need to defend themselves from predatory species. Hawaiian endemic species have been in a constant state of threat since the first introduction of non-native invasive species, whether it be an aggressive plant, a terrestrial mammal, or a mosquito.

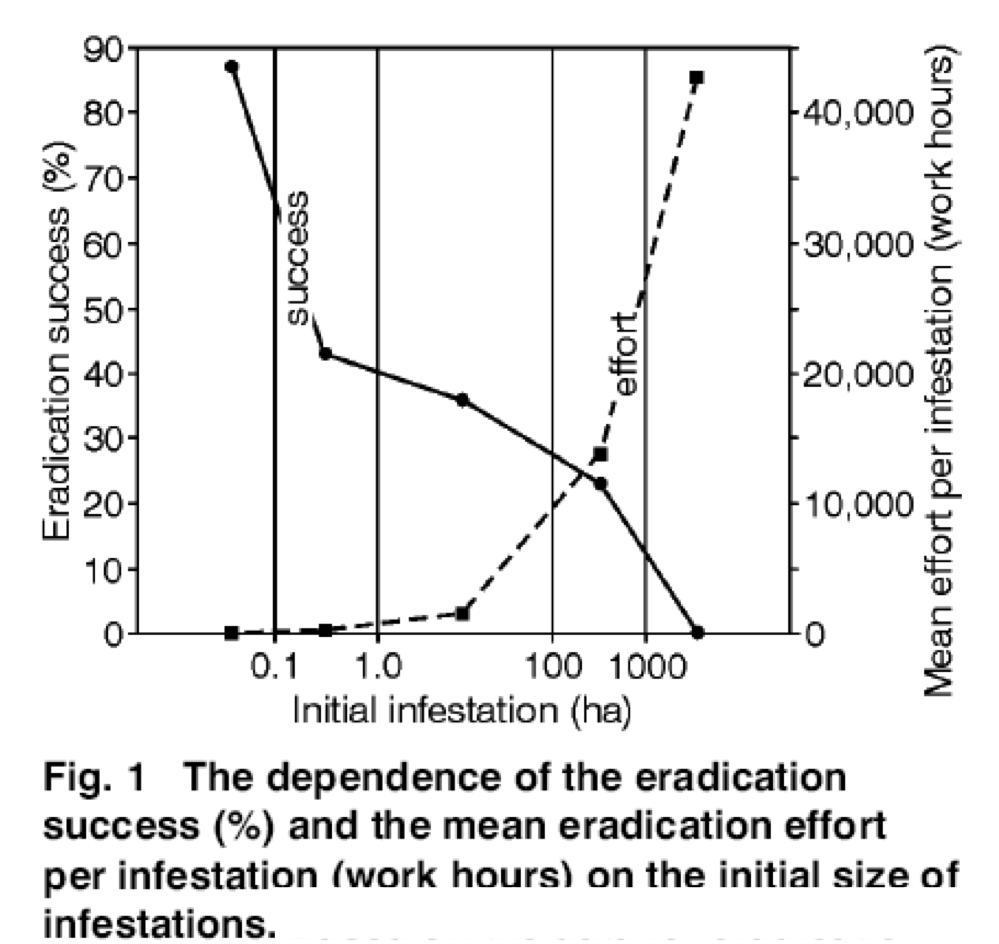

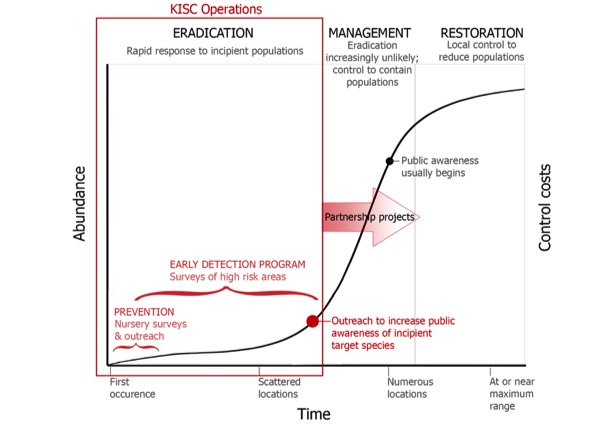

Invasive species account for more than $130 billion in U.S. annual losses2. This money is distributed through losses in agriculture, biodiversity, forest habitat, as well as human health. In Hawai‘i and the U.S. at large, most of the invasive species money is spent on management, when more of it should be spent on prevention. If we can stop the spread before it begins, or even stop the new introduction of invasive species, we’d be saving a lot of time, money, and effort. But most importantly, we’d be saving the forests from becoming threatened in the first place and likewise, we’d be saving our food sources from becoming vulnerable to new pests. The fastest, least expensive, and most effective way of treating invasive species is to spend money and efforts in prevention or early eradication.

Have you ever driven across the border into California? In my experience, it is comparable to the time I tried to cross back into the States from Mexico, without my passport (this story is interesting, but not applicable to invasive species). The point is, those California border agents definitely instilled fear in me. With a drill Sargent tone of voice, they asked me very probing questions about what was traveling with me in my car. One particular time I happened to be eating an apple as I pulled up to the border. Grown in California, purchased in New Mexico, and halfway consumed in Nevada, there was no way the other half of my apple was allowed back into California. I was shocked at how strict they were!

But the truth is, California has to be strict. According to the USDA, California ranks #1 in fruit production in the nation, it has more vegetable growing acreage than any other state, and grows more than 80% of all the almonds in the entire world3. California has a lot at stake when it comes to invasive species. No matter how big or small, if the wrong pest is accidentally introduced, it could cause significant damages to agriculture production. Spending money at the border with prevention, also known as biosecurity; Hawai‘i needs more of this.

Now, just think about Kaua‘i’s unique and endangered forests as if they were California’s agriculture industry. While having food is, of course, incredibly valuable, so is biodiversity! Let’s take Big Island for example. Currently Coqui frogs, Little Fire Ants (LFA), and Miconia are widespread in multiple habitats surrounding the island. Coqui and LFA are greatly impacting tourism and housing values. Miconia infests more than 40,000 acres of native forest habitat, displacing native plants, birds, and invertebrates. In addition to Coqui, LFA, and Miconia, there has been a recent discovery of an invasive pathogen called Rapid Ohia Death (ROD). ROD has the potential to wipe out every Ohia Lehua forest on the island, and potentially every other island. The race for ROD research and resources is one of the most important environmental issues facing the state right now. As current research demonstrates, once an Ohia tree becomes infected, the entire tree will die with in two weeks. Furthermore, with the recent introduction of Dengue Fever to Big Island, invasive species have now come to threaten not only biodiversity and native forests, but also the agriculture and health care industries as well.

The problem is, we are spending money after these invasive species have not only been introduced, but after they have already spread. At KISC, we target incipient species. We are currently funded to only target any new invader that has the potential to become an aggressive and destructive invasive species.

We need more resources in prevention and biosecurity. In 1999, when President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order (EO) 13112, the National Invasive Species Council was established. Following this EO, invasive species were finally recognized as a significant threat, and on the national radar for federal and state budgets. Yet even still, in fiscal year 2000 Hawai‘i only spent $1.6 million dollars on invasive species activities, compared to the $127.6 million Florida spent, and the $87.2 million California spent4. Kauai has some of the last forests where native and endangered birds and plants have a fighting chance. A lot of the species that are already widespread on the other islands, still have a chance to be eradicated here. As one of the smallest islands, with a small Department of Agriculture staff, and one of the smallest invasive species budgets, we’ve got our work cut out for us. KISC looks to the community to help us with keeping an eye out for invasive species around the island, but the community can also make changes in budgets and legislature with their right to vote and the will to stand up to protect Kaua‘i.

References

DLNR1 – http://dlnr.hawaii.gov/hisc/info/